Portrait of René Descartes (1596-1650) by Fran’s Hals 1649. Statens Museum for Kunst, Coppenhagen

No one comes close to the ingenuity of the man who changed our fundamental understanding of nature (and ourselves) like the legendary French philosopher, scientist and mathematician Rene Descartes. He was not an inventor like Graham Bell or Galileo but he did something iconic. At a time in history when curiosity was suppressed in the name of conformity to the authority of religion and prevailing philosophy, he was the first among (the other was Francis Bacon) to assert that: “There is need of a method for finding out the truth.” As one of the history’s most intriguing minds, Descartes laid the foundation to reason and critical thinking.

What happens when a random flash of insight is coupled with an incredible capacity to comprehend and expand upon it? Rene Descartes life is filled with such impactful epiphanies. After determining that the typical path to a standard career wasn’t for him, Rene Descartes made a huge (and uncharacteristic) leap of faith by moving to Holland to join the military. Quickly realizing that he wasn’t necessarily cut out to be a soldier, Descartes made his mark as an engineer, relying on his keen mathematical sense rather than his physicality.

Years of intense education convinced him of only one thing – he could learn more by way of his own philosophy and studying science alone, without the distraction of textbooks and the authority of teachers. He was right. One seemingly ordinary day, as Descartes lay in bed daydreaming, he idly watched a fly buzz about his room. He came to a realization at that instance – the position of the fly at any time could be represented by three numbers – providing a distance from the three walls that met in the corner. We know these today as the Cartesian co-ordinates. In school, we learned that any point on a graph is represented by two numbers, corresponding to the distance along the x axis and up the y axis.

Years of intense education convinced him of only one thing – he could learn more by way of his own philosophy and studying science alone, without the distraction of textbooks and the authority of teachers. He was right. One seemingly ordinary day, as Descartes lay in bed daydreaming, he idly watched a fly buzz about his room. He came to a realization at that instance – the position of the fly at any time could be represented by three numbers – providing a distance from the three walls that met in the corner. We know these today as the Cartesian co-ordinates. In school, we learned that any point on a graph is represented by two numbers, corresponding to the distance along the x axis and up the y axis.

What did this mean? It meant that any shape could be represented with just a set of numbers related to one another by mathematical equation. The discovery, once published, transformed mathematics from its roots. This discovery made geometry able to be analyzed using algebra – the consequence of which went on to inspire both the theory of relativity and quantum theory in the twentieth century.

There is need of a method for finding out the truth – René Descartes

You might also remember using the beginning of the alphabet (a, b, c) to represent known quantities, and letters at the end of the alphabet (especially x, y, z) to represent the unknown quantities. It was Descartes’ who inscribed this language into mathematics.

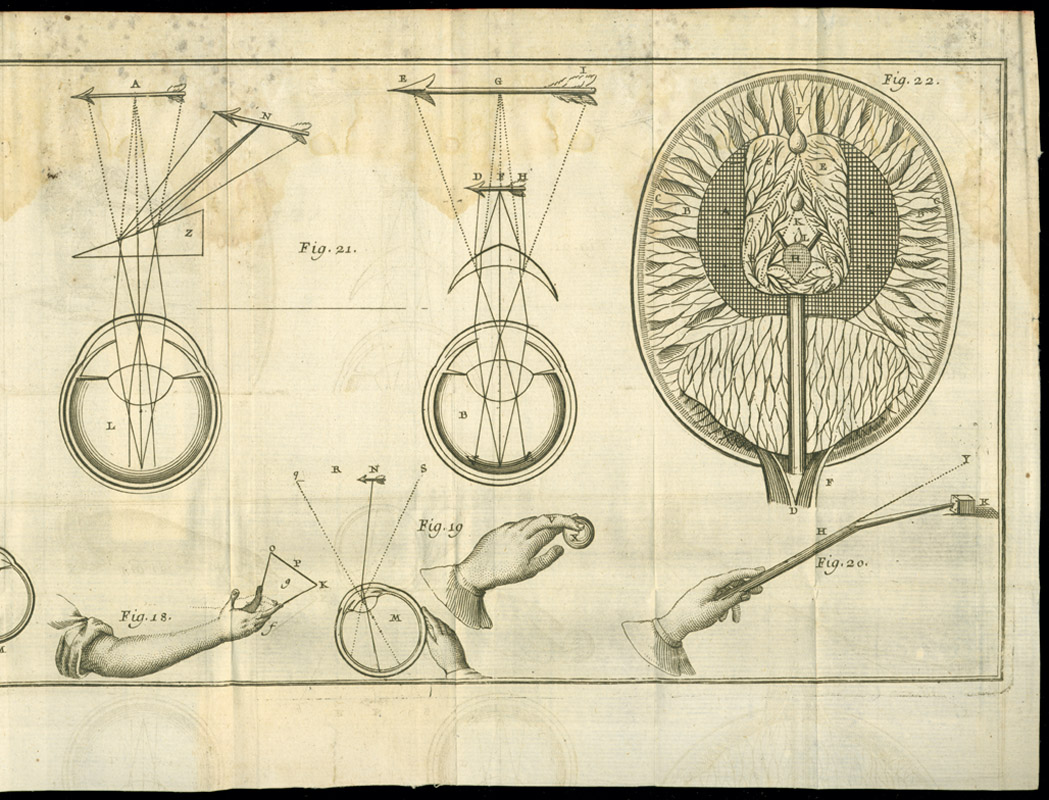

René Descartes, L’homme…. These drawings show the influence of Descartes’ knowledge of mathematics and geometry on his perception of how the body works.

At the age of 24, Descartes left the military in 1620 and sold his estate he’d inherited from his mother, using the proceeds to finance his continued dedication to independent studies. From 1629 to 1633, Descartes worked tirelessly on his treatise Le Monde ou Traité de la lumière, which detailed his ideas on physics. Unfortunately, in a seemingly knee-jerk reaction, Descartes stopped publication immediately upon hearing news of Galileo’s trial for heresy as he was convicted for Copernican beliefs. Luckily Descartes was later able to recycle much of his work in different projects.

René Descartes, L’homme…. “…I desire you to consider, I say, that these functions imitate those of a real man as perfectly as possible and that they follow naturally in this machine entirely from the disposition of the organs-no more nor less than do the movements of a clock or other automaton, from the arrangement of its counterweights and wheels.”

![René Descartes, Renatus des Cartes de Homine figuris (Lugduni Batuorum [Leyden]: Apud Franciscus Moyardum & Petrum Leffen, 1662). In this work Descartes posited that much human behavior can be explained by mechanical responses rather than the actions of the soul. Through a better knowledge of the mechanics of the body, he hoped to cure and prevent disease, and even to slow aging.](http://rajeevkurapati.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/07/rene-descartes-3.jpg)

René Descartes, de Homine figuris. In this work Descartes posited that much human behavior can be explained by mechanical responses rather than the actions of the soul. Through a better knowledge of the mechanics of the body, he hoped to cure and prevent disease, and even to slow aging.

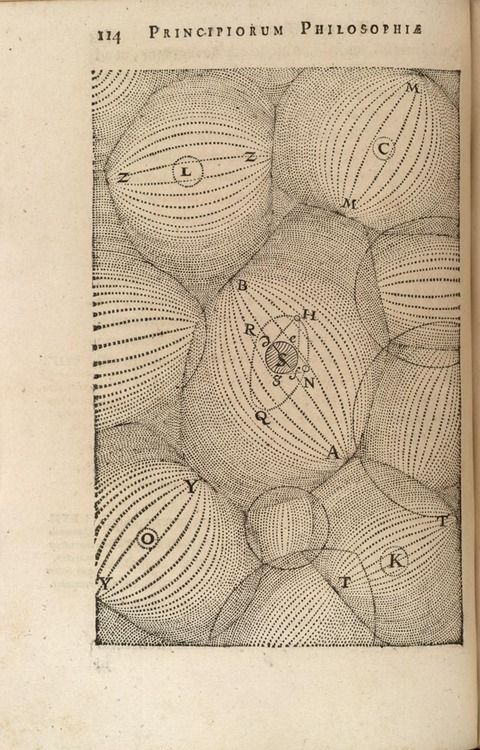

According to René Descartes (1596-1650), the universe operated as a continuously running machine which God had set in motion. Descartes argued that the universe was composed of a “subtle matter” he named “plenum,” which swirled in vortices like whirlpools and actually moved the planets by contact. Here, these vortices carry the planets around the Sun. The vortex theory did not require a gravitational force, so when Isaac Newton proposed a universal force of gravitation in 1687, many preferred Descartes’ explanation, because Newton’s force was not a mechanical force. However, Newton’s gravitational theory worked so well in explaining such matters as the tides, the shape of the earth, and the variation in pendulum clocks with changes in latitude, that cosmic vortices were in general dissipation by 1750, and Descartes’ swirling matter swirled itself into total and complete invisibility by the end of the century.

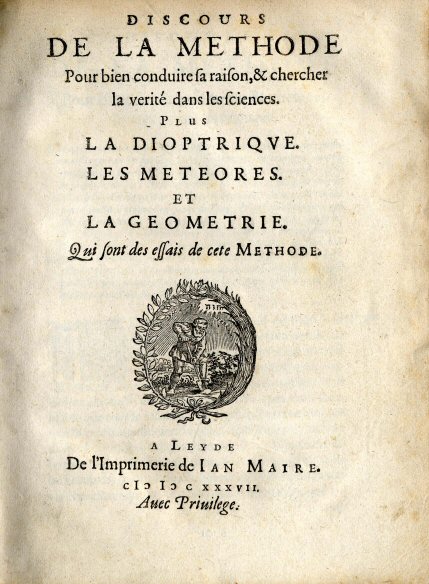

The Discourse on the Method (French: Discours de la méthode) is a philosophical and autobiographical treatise published by René Descartes in 1637. Its full name is Discourse on the Method of Rightly Conducting One’s Reason and of Seeking Truth in the Sciences. The Discourse on The Method is best known as the source of the famous quotation “Je pense, donc je suis” (“I think, therefore I am”), which occurs in Part IV of the work. (The similar statement in Latin, Cogito ergo sum, is found in Part I, §7 ofPrinciples of Philosophy.)